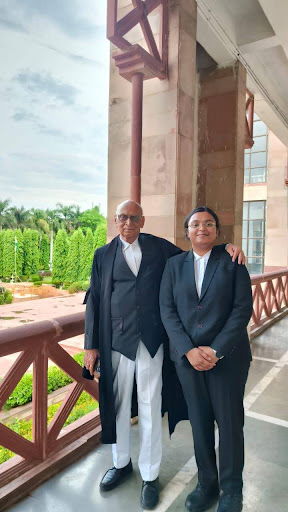

Senior Advocate Kailash Narayan Gupta, High Court of Madhya Pradesh on What it Truly Means to Uphold the Rule of Law

Interview conducted by Tanushree Vijayvargiya as a part of her Campus Leaders Program.

In the complex world of civil litigation and constitutional remedies, few voices carry as much weight as that of Senior Advocate Kailash Narayan Gupta Sir With an illustrious career spanning over 53 years at the Bar.

Sir has consistently stood out for his mastery over civil disputes and writ jurisdictions, especially in navigating the nuanced intersection of individual rights and state accountability.

Designated as a Senior Advocate of the High Court, he is widely respected not only for courtroom clarity and legal strategy, but also for a deep sense of procedural fairness and judicial discipline.

His arguments are known to be sharp, structured, and grounded in both law and principle — qualities that have earned him the confidence of clients, colleagues, and the Bench alike.

In this exclusive conversation, we explore not just the highlights of a remarkable legal journey, but the mindset and methods that have helped Sir, thrive in one of the most intellectually demanding areas of law.

From early lessons to present-day reflections, this interview offers timeless insights for law students, litigators, and all those who wish to understand what it truly means to uphold the rule of law.

What inspired you to pursue law, and was there a defining moment that confirmed this was your calling?

“My father wanted me to join law, since during my time (1950 to 70), it was considered a very respectable noble profession, which brought a lot of respect, and hence I followed it on his wish and thankfully it worked out in my favour.” I joined law college in 1968, and graduated in 1971.

At the time, the idea of law as a profession was not only about career security but was deeply connected to the concept of public service and social standing. While initially, my entry into law was a decision guided by my father’s aspirations for me, it slowly began to resonate with me at a personal level.

The defining moment came gradually—when I began understanding that law is not just about books or rules but about people, justice, and social order. The transformation from mere obligation to genuine passion happened as I immersed myself in my studies and experienced the real world of advocacy.

Over time, I realized I had found not just a profession but a lifelong purpose.

How did your time in law school shape your thinking — both as a student of the law and as a future litigator?

“Earlier I wasn’t comfortable and later I got comfortable, and today I am very grateful that I did it because now the reputation and respect I have earned is through this profession.” My law school years — from 1968 to 1971 — were not just about education but about formation of identity and perspective.

That era was crucial in India’s legal history — many key legislations were still maturing, and we, as students, were part of a generation that engaged with the law in its rawest, evolving form. With no digital aids like Google or online libraries, our learning demanded sincere, independent effort.

Sitting through long texts, deriving meaning without instant references, and trying to understand how Indian jurists were interpreting the law taught me a valuable skill — to think for myself. “Taking the terms and developing your own interpretation of law of what you read, what you learnt and what the jurists had to bring shaped my outlook to always look out for newer meaning and possibilities.”

It is this foundation of thought — to analyze, to seek more — that later prepared me for litigation and for the unpredictability of court practice.

What were the most pivotal moments early in your legal journey that laid the foundation for the career you have today?

“The reason why I chose to go into civil litigation was coincidentally because my senior or mentor practiced in civil litigation himself. He was my ideal and I learnt a lot from him.”

During my graduation itself, I began practicing under him, he was a renowned advocate in civil law — and the exposure I received working with him became the turning point of my early career. After graduating in 1971, I fully devoted myself to the field of civil litigation, and thankfully (chuckles), it worked in my favour.

The opportunity to learn directly from courtroom experiences, handle real case files, and understand how civil law operated in actual practice helped me transition smoothly into independent practice. I observed court proceedings diligently, and those early years shaped how I prepared my cases — not just legally but strategically.

I watched for what mistakes others made, noted how judges responded, and trained myself to avoid the common pitfalls. That early discipline became a habit — one that has served me every day in court.

Was there a particular case that became a turning point for you — one that tested or transformed you as a lawyer?

Since beginning my journey under a senior and eventually starting my own practice, my learning curve has always been sharp and consistent. I spent my early years closely observing court proceedings, which refined both my research and drafting skills. Watching the courtroom in action helped me identify common pitfalls and areas where lawyers were often questioned or faltered.

I made mental notes to avoid such errors, and over time, precaution became second nature. During my practice, there were many instances where judges demanded immediate answers — situations that tested me, but also shaped my ability to think quickly and respond with presence of mind.

These moments deepened my focus on framing better questions and strengthened my commitment to solid, well-grounded research.

The title of ‘Senior Advocate’ is both prestigious and earned. What does it mean to you personally, and how did you reach this milestone?

Being designated as a Senior Advocate brings with it a heightened sense of responsibility — towards the court, the litigants, and oneself. Personally, it demands greater caution, articulation, attentiveness, and observation. Towards the court, a Senior Advocate serves as a bridge between the judiciary and the general public — not just as a representative, but as a facilitator of justice.

We assist the court in arriving at decisions and are expected to ensure that no stance we take contradicts established precedent or the spirit of the law.

The court often seeks our suggestions, and at times, may even pass judgments contrary to our arguments. Yet, our duty is to offer honest legal guidance, even if it goes against our client’s interests. We are seen as neutral officers of the court, and with that comes the obligation to prioritize the integrity of the law above all else.

I recall a particular case where the court was inclined to grant relief in my favor. However, the remedy being considered did not align with existing legal provisions. When the judge asked if I was satisfied, I replied, “If Your Lordship is giving it, I am happy.”

He further questioned whether the proposed judgment was in accordance with the law or if an error was being made. At that moment, my responsibility as a Senior Advocate required me to tactfully guide the court toward the correct legal position — even though it meant the outcome might not favor me.

This incident exemplifies how the role of a Senior Advocate is not merely about representation, but about upholding the law itself. With seniority, the expectations and weight of one’s stance in the court multiply many times over.

Writ jurisdiction is a powerful tool. What makes a strong writ petition in your view — in both drafting and oral argument?

“You should be well known and verse with rule of drafting subject, and latest judgements — then only will it be a good draft or considered one. In my view, a powerful writ petition begins with deep familiarity with the relevant drafting rules and the most recent judgments — particularly those shaping constitutional and administrative law.

Drafting is not mechanical; it is strategic. The facts must be aligned with constitutional provisions and supported by established judicial precedents. Without this foundation, the petition cannot hold weight. As for oral submissions, one must go beyond just reading the file.

An advocate should anticipate the likely concerns of the Bench — what they might ask, where they might probe — and must be prepared with clear, lawful, and respectful responses. Writs are not casual pleadings; they demand precision and preparation in equal measure.

For oral arguments, it’s essential to anticipate the court’s expectations: “We should know what the judges wants and will ask and if asked we should not only be able to answer it but also be well prepared for it.”

Can you share a writ matter where the High Court’s intervention made a lasting impact on someone’s rights or life?

“Some public interest litigation, which are going on — recently only, there is a case going on in the High Court of Madhya Pradesh, Gwalior Bench, wherein there are interim orders passed against it. It is against solid waste being disposed of by companies and hence it is acting as a precedent and is helping citizens as well as the city at large.”

This particular PIL currently before the Gwalior Bench is a clear example of how the High Court’s writ jurisdiction can serve not just individual justice, but the public interest. The matter deals with improper disposal of solid waste by companies, which posed serious environmental and health concerns.

The Court passed interim orders against this practice, and the case is now shaping into a precedent. It is already having a practical effect — compelling companies to reassess their waste management protocols — and is offering relief to ordinary citizens and contributing to environmental governance. This is the true power of writ jurisdiction — when used responsibly, it becomes a tool of systemic reform.

Civil litigation often involves complex facts and long timelines. How do you approach evidence and procedural strategy in such cases?

“As an advocate, in order to prepare for civil cases which require and have long documents to read and prepare, the first step comes right after we take any case — we have to first assess which case will be called for hearing first and which will not or be assigned a later date.”

This preliminary assessment is vital because it lets us allocate our preparation time efficiently. “This is not easy but is manageable and can be understood with practice — by the type of case, the type of relief sought from it, etc.” If a case is likely to be listed early, then it becomes a priority, and preparation must begin accordingly.

“So, according to us, if a case is coming first for hearing, we should be cautious about it and prepare accordingly. For preparation, the first step is acting from finding and establishing a concrete, solid and clear timeline of facts and circumstance.”

High Court matters, particularly in civil appeals or interim reliefs, demand clarity of facts — both for the advocate and for the judge. “Step 2 is establishing areas of visible conflicts (chuckles) — even with so many years of practice, it is still interesting for me to look over a case and identify the fallouts and mistakes in it.”

Once the facts and conflicts are identified, then comes the law — “the relevant laws and sections. This is important because you can’t leave anything, and sometimes you might be dealing with many statutes or procedural law at once, so it is important to approach it one by one.”

“Then comes associating your findings with each fact in the timeline.” That linkage of law and fact strengthens the narrative of your case.

But preparation doesn’t end before the hearing — it evolves during the hearings too. “Once the hearings start, you have to make detailed aftermath notes about how the court day went, what were the facts in the timeline you established before the court of law, where were you asked to revert back, or where you weren’t able to answer or were asked an extension, what were some points the opposing counsel made that made you aware of a page unturned.”

“And then as motion hearings pass, you keep on adding documents and case laws and defining your arguments, and it goes all the way till the case is finally disposed of.” That is the discipline required in civil litigation — it’s not a sprint, it’s a continuous process of observation, refinement, and endurance.

How has civil litigation evolved in recent years — especially with digital records, ADR mechanisms, and changing client expectations?

“Public are more vigilant about their rights and hence are moving towards court for seeking remedies. Earlier they were digesting and tolerating any wrongdoing that were induced towards them, now they are remedy to approach the court for redressal.”

The biggest shift I’ve noticed is in the attitude of the public. There is far greater awareness of one’s legal rights today than there was in earlier decades. People no longer passively accept injustices — they seek redress. And with that shift, the role of the advocate has become even more pivotal.

“For us advocates, they can appear in person, and can’t appear for others, so we are there for them and have been in our profession with more responsibility for representation.”

Our responsibilities have expanded — not just to argue, but to guide, protect, and represent with integrity.

If you could introduce one reform in the legal or judicial system — or even in legal education — what would it be, and why?

“Constitution gives right and duties both. So we should discharge our duties assigned in a lawful, good manner, then we should expect our rights are not frustrated. We should not talk only about our rights — first we should discharge our duties which is helpful to all concerned.”

If I had to propose a reform, it would be a cultural and ethical one — a return to constitutional balance. Much of today’s discourse revolves only around rights — but the Constitution is not one-sided.

It also lays down duties. I believe our education system, both in law and general civics, must emphasize that — only by discharging one’s duties in a lawful, responsible manner can we expect to enjoy our rights meaningfully. This mindset shift will benefit not just the legal fraternity, but society at large.

What are the most common mistakes you see young lawyers make, and what advice would you offer to those just beginning their litigation journey?

“They feel they know everything — even we are not in the position to say we know everything. We also say ‘almost’, not everything. That is the mistake that should not be there. Always remain in learning mode.”

Overconfidence is the most dangerous pitfall for a young lawyer. The law is vast — no one can ever claim to have mastered it entirely, not even those of us who’ve been practicing for over 50 years.

It is this humility that keeps you sharp. The moment you start thinking there’s nothing left to learn, the decline begins. My advice is simple: remain teachable. Stay curious, stay grounded. The court will teach you — if you’re willing to listen.

What mindset or skillset would you advise young lawyers to develop today if they aim to lead in this profession tomorrow?

“Tolerance, patience to be maintained. Don’t be in a hurry — no shortcut is there for success. So go on discharging your duty with full devotion — you will get success.”

Litigation is not a race; it’s a calling. The younger generation often seeks quick results, but the legal profession doesn’t reward haste — it rewards perseverance. You must cultivate tolerance: the ability to wait, to fail, to try again. You must nurture patience: in the court process, in your personal growth, and in understanding the law.

Most importantly, never abandon duty. “Discharge your duty with full devotion,” and let time take care of the rest. Success in law, like in life, comes slowly — but it comes to those who earn it.

Disclaimer: Interviews published on Lawctopus are not edited thoroughly so as to retain the voice of the interviewee.

This interview is a part of our Star Interview series, conducted by the Campus Leaders at Lawctopus. Stay tuned for more!