Evidence Act | S.106 Cannot Be Used To Fill Gaps In Prosecution Case Without A Firm Foundation: J&K High Court

Reaffirming foundational principles of criminal jurisprudence, the High Court of Jammu & Kashmir and Ladakh has ruled that Section 106 of the Indian Evidence Act cannot be invoked to fill material gaps in the prosecution case unless the foundational facts necessary to shift the onus are first firmly established.

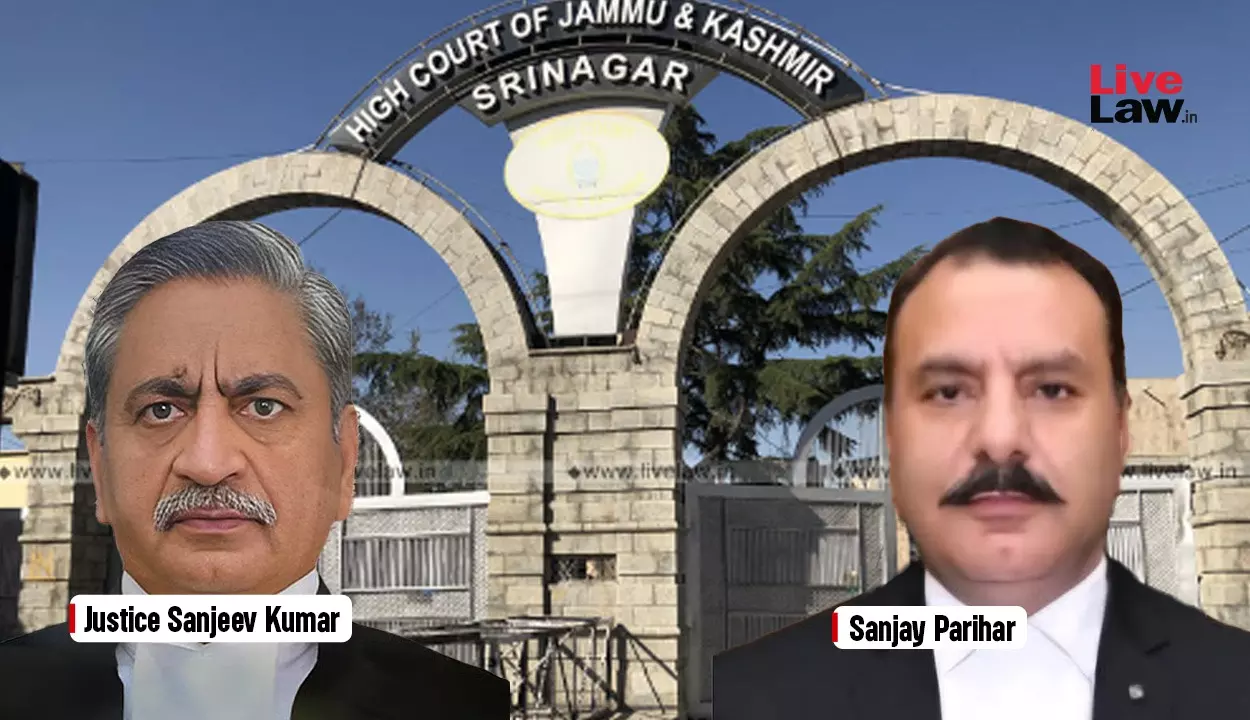

While acquitting accused Shamim Ahmad Parray @ Koka Parray and Mst. Gulshana, both convicted by a trial court for the alleged murder of Farooq Ahmad Parray in 2002 Justices Sanjeev Kumar and Justice Sanjay Parihar dissected the prosecution’s circumstantial evidence thread by thread and concluded that the conviction was built more on conjecture and suspicion than on any cogent or reliable proof.

Background:

The case arose from an incident when Farooq Ahmad Parray was found dead in his own home. His brother-in-law, PW-1 Gull Parray, discovered his body and immediately alerted police. The investigation soon turned toward Farooq’s wife, Mst. Gulshana, and her alleged paramour, Shamim Ahmad Parray, amid circulating rumours of an illicit relationship.

According to the prosecution, Gulshana facilitated Shamim’s clandestine entry into the house, whereupon he allegedly hit Farooq with a pestle and later strangled him. An FIR was registered under Sections 302/34 RPC.

In 2014, both were convicted and sentenced to life imprisonment. The present appeal challenged that conviction.

Court’s Observations:

Right at the outset, the High Court observed that the case rested entirely on circumstantial evidence and applied the principles laid down in Raj Kumar Singh v. State of Rajasthan and Sharad Birdhichand Sarda v. State of Maharashtra, which mandate that the chain of circumstances must be complete and must unequivocally point to the guilt of the accused.

The Court noted,

“Graver the crime, greater should be the standard of proof. Suspicion, however grave it may be, cannot take the place of legal proof.”

It stressed that Section 106 of the Evidence Act which allows courts to draw adverse inference when facts are within special knowledge of the accused—“cannot be used to make up for the failure of the prosecution to establish foundational facts.”

The Court found key prosecution witnesses to be unreliable. One of the crucial witnesses was the minor daughter of the deceased and Mst. Gulshana (PW-18), who initially failed to mention Shamim’s presence but later made contradictory statements.

“Her contradictory narration—claiming to have both peeped through the door and followed her mother—should have cautioned the trial court. This cannot be treated as a minor inconsistency, especially in a case based on circumstantial evidence,” the Court remarked.

The pestle allegedly used as the murder weapon was recovered from a shelf in the kitchen hardly a concealed location. The Court ruled,

“The place of recovery was accessible to one and all. Even medical experts admitted no blood stains were visible on the pestle at the time of examination. Yet forensic reports later claimed blood stains were found—an inconsistency the prosecution never explained.”

The alleged recovery of Shamim’s identity card from a pit dug in the courtyard was also doubted. The court observed that the photographs clearly showed the card visibly lying on the surface, yet the investigating officer had missed it during his first search.

“The timing and manner of recovery raises strong suspicion of planting,” the Court noted.

As for the two pits discovered on the property, the Court accepted the defence version that the Army had earlier searched the premises for weapons due to militant links within the family.

The prosecution claimed that the motive was an illicit affair. But this angle, the Court noted, only emerged after the arrest.

“Until April 5, 2002, the investigation had not established any evidence of an illicit relationship. The theory seems to have been retrofitted post-arrest,” the Court observed.

Though the post-mortem listed throttling as a cause of death, the Court noted,

“No evidence was collected to show bruising, nail marks, finger impressions or signs of struggle. The entire aspect of throttling was neither investigated nor explained.”

Finding that neither the recovery of the pestle nor the testimony of key witnesses nor the circumstantial evidence met the stringent standards of proof, the Court ruled,

“Once the foundational facts linking the accused are lacking, their silence or non-explanation cannot be held against them. Section 106 cannot be invoked to bridge gaps in the prosecution case.”

Accordingly, the High Court set aside the trial court’s judgment and acquitted both Shamim Ahmad Parray and Mst. Gulshana of all charges.

Case Title: Shamim Ahmad Parray Vs State of J&K

Citation: 2025 LiveLaw (JKL)