“Without Fear Or Favour”: A Deep Dive Into India’s Controversial Collegium System That Picks Judges But Resists Reform

India’s judicial collegium system, once a shield for independence, now faces strong criticism for its lack of transparency and diversity. CJI B.R. Gavai’s 2024 remark has reignited the demand for urgent reforms.

Thank you for reading this post, don’t forget to subscribe!

“Judges must be free to decide without fear or favour.”

This strong message was given by Chief Justice of India B.R. Gavai in May 2024. It was not just a formal statement but a bold comment on the ongoing problems in India’s judicial appointment process — the Collegium System.

While originally designed to shield the judiciary from executive pressure, the collegium now faces its own share of questions:

- Is it transparent?

- Is it fair?

- Is it still the best we can do?

This article unpacks the collegium system’s impact over the last three decades—drawing from judicial commentary, constitutional law, and data-driven research to assess how it has shaped the composition, independence, and credibility of the Supreme Court of India.

Has it strengthened the court or simply replaced the one form of bias with another?

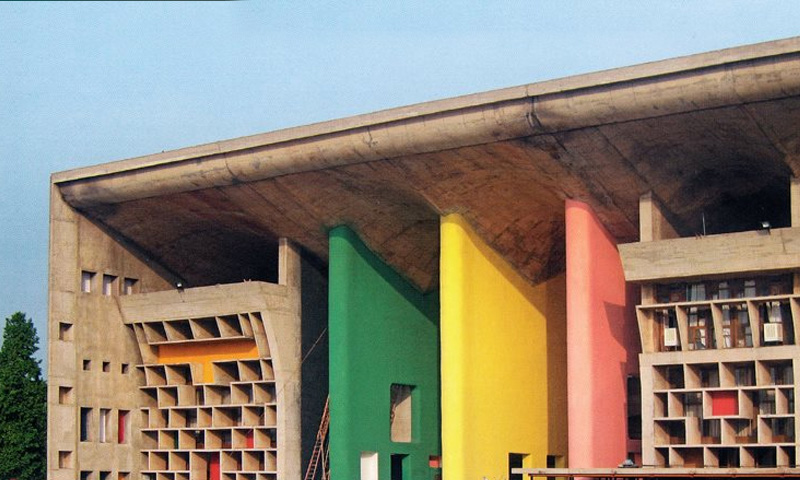

The collegium system, introduced through the landmark 1993 judgment in the Second Judges Case (Supreme Court Advocates-on-Record Association v. Union of India), marked a pivotal departure from the earlier era where the executive held dominant control over judicial appointments.

ALSO READ: Collegium System Shields Judiciary’s Autonomy Despite Flaws: Justice Surya Kant

This judgment, later fortified by the 1998 opinion in the Third Judges Case, effectively placed the power of appointment and transfer of judges in the hands of a select group of senior Supreme Court judges, led by the Chief Justice of India.

The shift was widely celebrated as a triumph for judicial independence, especially in the wake of politically motivated decisions from the past, such as the supersession of Justice H.R. Khanna during the Emergency. However, over time, the collegium system developed its own set of challenges that, while distinct from those of the executive-led model, are no less serious.

CJI Gavai’s recent remarks underscore the judiciary’s growing credibility crisis that “judges must be free to decide cases without fear or favour.” His remark came amidst growing unease over the erosion of public trust in the judiciary, especially when judges resign to contest elections or accept post-retirement positions offered by the government.

These patterns raise serious ethical concerns about institutional impartiality and create a perception that judicial roles may be influenced by political prospects.

In this climate of scrutiny, a comprehensive empirical dataset spanning 72 years (1947–2019) provides crucial insight into how the collegium system has impacted the composition of the Supreme Court. One notable trend is the sharp decline in the inclusion of judges with lower judiciary experience falling from 21% under the executive-led system to just 5% under the collegium.

Simultaneously, direct appointments from the Bar have increased, with only three such appointments made in 46 years of executive control, compared to five in just 26 years under the collegium.

The concerns voiced by CJI Gavai are not theoretical. In recent years, several high-profile instances have blurred the line between the judiciary and politics. Justice Abhay Thipsay, a former Bombay High Court judge, joined the Congress party after retirement and even appeared in court on behalf of political leaders.

Similarly, Justice C.S. Karnan, known for his controversial tenure in the Madras and Calcutta High Courts, made headlines by announcing plans to form a political party shortly after his retirement. Another example is Justice Kurian Joseph, who publicly criticized the judiciary’s functioning post-retirement and was involved in public debates with political overtones.

Such moves raise pressing questions:

If judges are seen as future politicians or government appointees, can they truly be neutral arbiters while still on the bench?

The spectre of post-retirement rewards or political ambitions undermines the perception of impartiality, a cornerstone of judicial legitimacy. When public confidence in judicial neutrality erodes, so too does the authority of the judiciary itself.

However, this surge in Bar appointments hasn’t translated to greater diversity. On the contrary, Judges appointed from the Bar tend to enjoy significantly longer tenures averaging 1,870 days compared to 1,160 days for those from the lower judiciary.

This limits the leadership and impact of career judges, reinforcing judicial elitism and narrowing the spectrum of courtroom experience. Such skewed representation may also lead to bias in favor of legal professionals within judicial decision-making, reducing the diversity of perspectives on the bench.

In terms of regional representation, the collegium system has created both positive shifts and new imbalances. During the executive era, four High Courts:- Bombay, Calcutta, Allahabad, and Madras dominated Supreme Court appointments, accounting for 45%. Under the collegium, this dropped to 30%, with broader inclusion of 19 High Courts.

Delhi High Court’s share rose from 2% to 9%, and smaller High Courts like Patna and Himachal Pradesh gained more visibility. However, Southern High Courts such as Madras, Karnataka, and Kerala saw a decline in representation, raising concerns about eroding linguistic and cultural diversity in constitutional interpretation.

The collegium’s failure to maintain consistency in judicial tenure further complicates the debate. Data reveals that the average tenure of Supreme Court judges has reduced from 2,350 days under the executive to 1,868 days under the collegium. The number of long-serving judges those exceeding 3,000 days has dropped from 27% to 5%, while those with short tenures (less than 1,500 days) have nearly doubled.

These figures suggest delays in elevation, likely due to rigid seniority rules, opaque deliberations, and internal lobbying. The consequence is not just administrative; it erodes continuity in constitutional jurisprudence and deprives the Court of experienced leadership capable of shaping doctrine over extended periods.

The attempt to reform the collegium via the National Judicial Appointments Commission (NJAC), introduced by the 99th Constitutional Amendment, was a significant milestone. The NJAC proposed to include members from the executive and civil society in the appointment process, aiming for broader accountability.

However, in 2015, the Supreme Court struck it down in what is popularly called the Fourth Judges Case, citing violation of the basic structure doctrine, particularly the principle of judicial independence. While the Court was right to guard against executive overreach, the decision also effectively closed the door on urgently needed reforms that could have balanced independence with transparency.

What emerges from this analysis is a paradox. The collegium has succeeded in insulating the judiciary from the executive, but it has failed to insulate itself from its own structural biases. It continues to function without formal criteria, without public reasoning for appointments or rejections, and without mechanisms to ensure diversity in region, caste, gender, or judicial background.

Its informality breeds suspicion, its opacity breeds distrust, and its resistance to reform breeds institutional fatigue. The legitimacy of the judiciary cannot rest solely on its independence from government; it must also arise from the people’s confidence in its fairness, openness, and inclusivity.

Reforming the collegium need not mean surrendering judicial independence. Rather, it means evolving towards a transparent, codified process that publishes detailed reasoning, ensures broader representation, respects judicial experience at all levels, and sets ethical boundaries on post-retirement engagements.

The credibility of the judiciary is too important to be left to custom and convention alone. As India moves deeper into the 21st century, the judiciary must rise to meet not only constitutional expectations but also democratic ones. A system meant to defend the rule of law must itself be ruled by principles of fairness, transparency, and accountability.

Only then can the words “without fear or favour” ring true not only from the bench, but in the hearts of the citizens it serves.

Conclusion

The judiciary stands as the last refuge of the Constitution the place a citizen turns to when all else fails. But that refuge only holds strength if it is anchored in trust. The collegium system, born out of the need to shield judges from executive interference, was a promise of independence.

Yet today, that promise is being questioned not because of outside interference, but because of silence within.

When appointments lack transparency, when diversity is sacrificed for convenience, and when the doors of opportunity open more easily for a few than the many, the judiciary risks drifting away from the people it was meant to serve.

Judicial independence cannot mean judicial isolation. It must be grounded in integrity, transparency, and accountability. A system that selects those who will interpret the Constitution must itself reflect the spirit of the Constitution diverse, inclusive, fair, and fearless.

The way forward is not to abandon the collegium, but to reform it to open its windows to light, to codify its values, and to reconnect it with the democratic ethos it was meant to protect.

The question, then, is not whether the judiciary should remain independent it must. The real question is whether it can be both independent and introspective. Because in a democracy, the strength of an institution does not lie in its power to silence criticism but in its willingness to evolve.

Sources Consulted

- Tripathy, R., & Dhanee, S. (2020). An Empirical Assessment of the Collegium’s Impact on Composition of the Indian Supreme Court. National Law School of India Review, Volume 32, Issue 1, Article 6.

- NDTV (2024). Judges Must Be Free: Chief Justice’s Big Remark on Collegium System. Link

- AdvocateKhoj. (n.d.). Understanding the Collegium System of Judicial Appointments. Link

- Vajiram & Ravi. (n.d.). Collegium System and Appointments in Judiciary. Link

AUTHOR

Daman Kashyap

CT Institute of Law 2024-29

First Year Law Student

Would You Like Assistance In Drafting A Legal Notice Or Complaint?

CLICK HERE

Click Here to Read Our Reports on CJI BR Gavai

Click Here to Read Our Reports on Collegium System

FOLLOW US ON YOUTUBE FOR MORE LEGAL UPDATES